At its heart, contract law runs on a simple, powerful idea: mutual consent. Both parties have to willingly agree to the terms, creating a true "meeting of the minds." But what happens when one party's signature is the result of a threat or intense pressure? That's where the legal concept of duress comes into play.

Think of it as a forced handshake. The signature is on the paper, but the genuine, voluntary agreement needed for a binding contract just isn't there. Because of this, any contract signed under duress is voidable—meaning the wronged party can choose to cancel it.

Unpacking the Concept of Duress in Contract Law

Duress completely undermines the principle of voluntary agreement. It creates a situation where one person signs not because they agree, but because they feel they have no other realistic choice. The law essentially recognizes their signature as invalid by saying, "I signed, but I was coerced."

Here’s a classic example. Imagine a supplier suddenly tells a small business they’ll halt all critical deliveries the day before a huge product launch. The catch? The business owner must first sign a brand-new contract with a 30% price increase. Facing financial ruin, the owner signs. No one was physically threatened, but the economic pressure was so immense and wrongful that it constitutes duress.

The Line Between Hard Bargaining and Unlawful Pressure

It's crucial to understand that duress isn't just tough negotiation. Business is competitive. Aggressive sales tactics or leveraging a strong market position are usually fair game. The law expects companies to hold their own during hard bargaining.

Duress crosses the line when the pressure becomes illegitimate. For a court to recognize duress, a few key elements usually need to be present.

Here is a quick overview of what a party typically needs to prove in a duress claim.

Key Elements of a Duress Claim at a Glance

| Element | Description |

|---|---|

| Illegitimate Pressure | The threat or action must be wrongful. This could be a threat to commit a crime, a tort (a civil wrong), or even a bad-faith threat to breach an existing contract. |

| Causation | The wrongful pressure must be a direct and significant reason the victim entered into the contract. They have to show they wouldn’t have agreed otherwise. |

| Lack of Reasonable Alternative | The victim must prove they had no other practical or viable way out of the situation except to give in to the demand. |

These components help courts distinguish between everyday business pressure and genuine, unlawful coercion that can invalidate a contract.

A contract entered into under duress is considered voidable. This gives the innocent party the power to either affirm the contract and stick to its terms or rescind (cancel) it, effectively wiping the slate clean.

Why Duress Matters in Business

Understanding duress in law of contract is essential for any professional. It acts as a shield, protecting businesses from exploitation and ensuring that agreements are built on a foundation of fairness.

Knowing the red flags of duress can stop you from being pushed into an unenforceable agreement. It can also give you a legal way out if you've already been coerced. To get a better handle on this, it's helpful to learn more about what it means to sign a document under duress. Ultimately, this knowledge reinforces the integrity of commercial deals, reminding us that true agreements are partnerships, not acts of submission.

How Duress Grew Up: From Physical Threats to Financial Pressure

The idea of duress in contract law didn't start in a modern courtroom. Its origins are much more visceral, tied directly to threats of actual, physical harm. For centuries, the only kind of coercion the law really cared about was the most obvious and brutal kind. To get a contract thrown out for duress, you had to prove a legitimate threat of death or serious injury.

Think of a landowner in the Middle Ages, a sword at his throat, being "asked" to sign over his castle. This is the classic, old-school picture of duress to the person. It's straightforward, terrifying, and leaves zero doubt the agreement wasn't voluntary. The law was simple and direct: your signature was meaningless only if the choice was to sign or get hurt.

That black-and-white approach worked well enough for a while. But as business became more sophisticated, so did the ways people could force a deal. The industrial revolution and the birth of complex commerce introduced new kinds of power. People figured out you could ruin a competitor without ever throwing a punch.

The Shift from Fists to Finances

The legal system was slow to catch on. For a long time, the courts just didn't buy that a threat to your property or business could be as coercive as a physical one. They drew a hard line: a threat against you was duress, but a threat against your wallet was just seen as the rough-and-tumble "ordinary pressure of business."

But this view started to look pretty out of touch as commercial relationships grew more complex. What happens when a massive company threatens to unlawfully withhold critical supplies from a smaller business, essentially choking it into signing a terrible contract? There's no physical violence, but the pressure is immense and the choice is anything but free. Is that not coercion?

This growing gap between old legal rules and new business realities created the perfect conditions for a major update to the duress in law of contract.

The Birth of Economic Duress

The real change happened when judges started to admit that illegitimate economic pressure could be just as overpowering as a physical threat. This new concept, economic duress, acknowledged that a threat to someone's financial survival could completely erase their ability to choose freely.

This doctrine didn't just appear out of nowhere; it was hammered out in a series of landmark legal fights. The idea really took hold when the House of Lords gave it official recognition in the early 1980s. Cases like Universe Tankships Inc of Monrovia v International Transport Workers’ Federation (1983) formally established that threatening to break an existing contract could be economic duress, giving the victim a way out. This was further solidified in the early 1990s with cases like Dimskal Shipping Co SA v International Transport Workers Federation (1992). You can get a deeper look into these pivotal legal developments to see how the courts settled the matter.

This was a huge leap forward. It dragged contract law into the modern world, where the real leverage is often financial, not physical.

Today, economic duress is an essential part of contract law. It acts as a crucial protection against predatory business tactics where one party uses their power to force a deal through unfair financial pressure.

The journey from only recognizing physical threats to including economic coercion shows how the law can adapt. It makes sure the fundamental principle of genuine consent stays protected, whether the pressure comes from the threat of a fist or the threat of financial ruin. Understanding this evolution is the key to seeing how duress applies in today's business world.

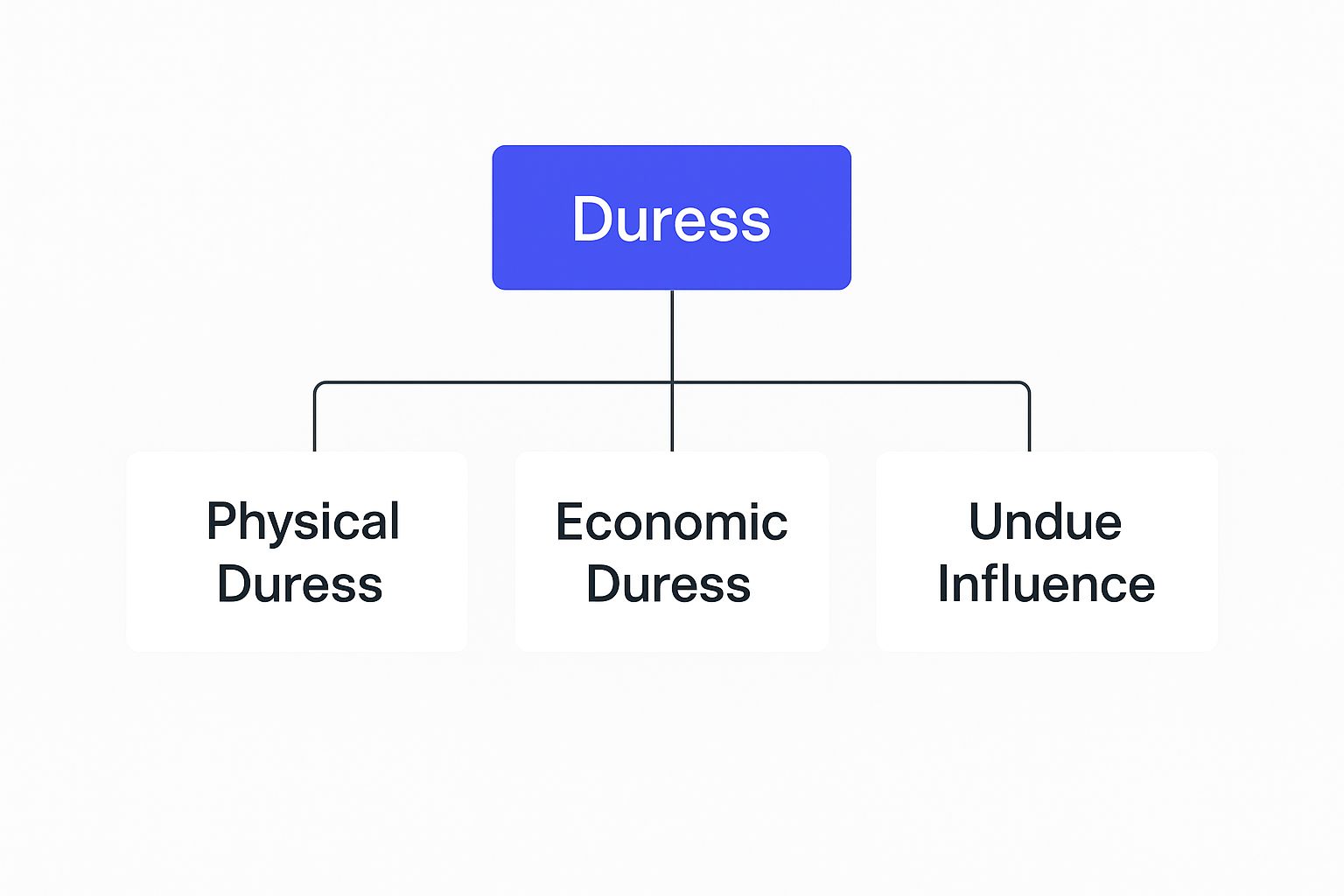

Understanding the Main Types of Duress

The idea of "duress" in contract law isn't a single, one-size-fits-all concept. It’s more like a family of related pressures. While they all look a bit different, they share a common DNA: forcing someone into a contract they wouldn't have otherwise signed.

To really get a handle on duress in law of contract, you have to know how to spot its different forms. These coercive tactics fall into a few key categories, each targeting a different part of a person's life or business. Learning to recognize them is the first step toward protecting yourself from illegitimate pressure during negotiations.

The image below gives a quick visual breakdown of how coercion can poison a contract.

This shows that everything from direct physical threats to more subtle financial arm-twisting is recognized by the courts as a potential reason to void an agreement. Let’s unpack each one.

Duress to the Person

This is the most direct and oldest form of duress—the classic "gun to the head" scenario. It’s all about threats of physical violence, harm, or imprisonment aimed at you or someone close to you, like a family member.

Imagine a business partner threatens to hurt you if you don't sign over your company shares for pennies on the dollar. The threat doesn't even need to be carried out. Just the fact that it was made is often enough to invalidate your consent.

The legal standard here is pretty straightforward: any threat of unlawful physical violence that pushes someone into an agreement makes that contract voidable. The pressure doesn't have to be the only reason they signed, just a significant one.

Duress of Goods

This type of duress happens when someone unlawfully takes, holds, damages, or threatens to destroy your property to force you into a deal. In short, they’re holding your belongings hostage to get what they want.

Think about a mechanic who just finished repairing your company's only delivery van. When you show up to pay the agreed price, he refuses to hand over the keys unless you also sign a brand-new, overpriced maintenance contract. Your business can't run without that van, so you cave and sign. That’s a clear-cut case of duress of goods.

Economic Duress

Economic duress is, by far, the most common form you'll see in the business world today. This is when one party uses illegitimate financial pressure to corner another party, leaving them with no real choice but to agree. It goes way beyond the normal hardball tactics of negotiation.

For a claim of economic duress to hold up, you generally need to prove a few things:

- Illegitimate Pressure: The threat itself has to be wrongful. This often looks like a bad-faith threat to breach an existing contract. For example, a critical supplier threatening to cut off deliveries unless you accept a surprise 25% price hike, knowing it will shut down your production line.

- Compulsion of the Will: The pressure must be so intense that it crushes your ability to choose freely. You aren't really agreeing—you're just submitting to the demand to avoid a disaster.

- Causation: The illegitimate pressure must be a major reason you entered into the contract.

A classic example is a construction company deep into a time-sensitive project. Their sole concrete supplier, knowing the company faces huge penalties for delays, suddenly threatens to stop all shipments unless the price is doubled. With no time to find an alternative, the company agrees. That new agreement was born out of economic duress and is likely voidable.

Why Acting Quickly Is Crucial for Duress Claims

In the world of contract law, when it comes to a claim of duress, time is absolutely not on your side. Once the illegitimate pressure is off the table—the threat has passed, the coercion has ended—a clock starts ticking. A contract you signed under duress is voidable, not automatically void. This is a critical distinction, as it puts the power in your hands to either kill the deal or accept it.

But that power has a shelf life. The law fully expects you to act decisively once you're free from whatever influence forced your hand. If you stay quiet, keep performing your duties under the contract, or just drag your feet, your inaction sends a very powerful message.

This is a legal principle known as affirmation, or ratification. By not challenging the agreement promptly, you're essentially telling the court, "Look, even though I was backed into a corner, I've decided I can live with this deal now that I'm free." That choice, whether you make it actively or just by waiting too long, can permanently lock in the contract and wipe out your right to claim duress.

The Danger of Delay and Implied Acceptance

In the eyes of the law, silence can easily be mistaken for consent. When you're no longer under duress but continue to collect benefits from the contract without a peep of protest, your actions speak much louder than your initial objections ever will. A court is likely to conclude you've simply chosen to live with the agreement, warts and all.

Imagine a small business that was strong-armed into a terrible supply contract. If they keep placing orders and paying invoices for months after the pressure is gone, it becomes incredibly difficult to argue they never really consented. Their own behavior suggests they’ve affirmed the very contract they now want to escape.

A classic case that drives this point home is the 1979 dispute North Ocean Shipping Co Ltd v Hyundai Construction Co Ltd. Hyundai threatened to walk away from a contract unless they were paid more, and North Ocean Shipping paid up under what was clearly economic duress. The catch? They waited eight months after the threat was gone to try and get their money back. The court ruled that this long delay amounted to an affirmation of the new terms, and their claim failed. You can read more about how this pivotal case shaped the rules on duress.

What Constitutes Prompt Action?

So, how fast is fast enough? There’s no magic number or universal deadline. What counts as a "reasonable time" to act is judged entirely on the specific facts of your situation.

The guiding principle, however, is crystal clear: you must challenge the contract as soon as you are practically able to. This means the moment the immediate threat is removed and you have a genuine opportunity to get legal advice or formally object.

Here are the first steps you absolutely must take:

- Protest in Writing: The second you are free from the coercive pressure, fire off a formal written notice. State in no uncertain terms that you entered the agreement under duress and you're reserving your right to have it rescinded.

- Get Legal Help Immediately: Don't put this off. A good lawyer can tell you how strong your claim is and walk you through the proper legal steps to void the contract.

- Stop Performing Under the Contract: If at all possible, halt any actions that would suggest you accept the deal, like making payments or accepting goods or services.

The core takeaway here is that the right to void a contract due to duress is fragile. You have to exercise it swiftly and decisively. Any hesitation can be fatal to your claim, turning a voidable agreement into a fully binding obligation.

The Real-World Impact of Duress Laws on Business

The concept of duress in law of contract isn’t just for dramatic courtroom showdowns. It casts a long shadow over everyday business, shaping how deals get negotiated, how companies manage risk, and how commercial relationships are built. These laws force courts into a delicate balancing act: they must shield vulnerable parties from being exploited, but without pulling the rug out from under the stable contracts that businesses depend on.

For business owners, understanding this balance is a huge strategic advantage. This isn't just about being fair; it's about building a predictable and reliable marketplace where deals are honored. The ever-present risk of a duress claim makes companies think twice about their negotiation tactics, ensuring that hard bargaining doesn't cross the line into illegitimate pressure.

How Duress Shapes Negotiation and Risk Management

The fear of a contract getting tossed out due to duress has a direct impact on how smart businesses operate. Prudent companies weave safeguards into their processes to head off any potential accusations of coercion. This proactive thinking is a cornerstone of modern contract risk management.

Common-sense preventative measures often include:

- Documenting Negotiations: Keeping a detailed record of discussions, offers, and counter-offers builds a clear paper trail. This demonstrates that the negotiation was a fair, voluntary back-and-forth.

- Allowing Time for Review: Rushing someone to sign a complex agreement is a major red flag for duress. Smart practice is to give the other party plenty of time to read, understand, and get their own independent legal advice.

- Confirming Understanding in Writing: It’s wise to include clauses where both parties state they have read, understood, and are voluntarily entering into the agreement. This adds a solid layer of protection.

From complex supply agreements to standard forms like rental agreement templates, knowing how duress laws apply is key to fair dealing. Ignoring these risks can drag you into costly, time-consuming legal battles. To get a better handle on these issues, our guide on effective contract dispute resolution offers some valuable strategies.

The Economic Logic Behind Duress Laws

At first glance, it might seem like duress laws are all about protecting the "little guy" from being bullied. While that's a huge part of it, there’s a deeper economic logic at work. A marketplace where contracts can be forced on people is fundamentally unstable and inefficient.

The ultimate goal of duress law is to promote economic efficiency by ensuring that contracts reflect a genuine "meeting of the minds." When deals are made voluntarily, they are more likely to create value for both parties and society as a whole.

But it's not always so simple. Academic research has dug into the messy economic effects of strictly applying duress rules. For example, some analysis suggests that if one party is threatening to breach a contract, refusing to enforce a modified deal signed under pressure can backfire. Sometimes, it leads to the contract being breached entirely—causing far more economic harm than if the coerced (but modified) agreement had been upheld.

Ultimately, duress laws are a vital, if imperfect, tool for keeping business dealings honest. They push for transparent negotiations and discourage predatory behavior, which helps create a healthier and more predictable environment for everyone.

How Businesses Can Mitigate Duress Risks

Knowing the theory behind duress in law of contract is one thing, but actively shielding your business from it is another ballgame entirely. The best defense is a good offense, which means building a contracting process grounded in fairness, transparency, and rock-solid documentation.

When you create a clear record showing that an agreement was voluntary, you build a powerful defense against any future claims of coercion. The goal is to make it obvious that every signature came from genuine consent, not improper pressure. A big part of this strategy isn't just knowing the law—it's also mastering the art of crafting winning business proposals that are inherently fair and invite genuine buy-in.

Proactive Strategies To Prevent Duress Claims

The smartest way to deal with a duress claim is to stop it from ever happening. By integrating a few key habits into your negotiation process, you can dramatically lower your risk and create a defensible record of all your dealings.

Start by weaving these measures into your process:

- Maintain Detailed Negotiation Records: Keep a meticulous paper trail of all communications—emails, meeting notes, revised drafts, you name it. This log paints a picture of good-faith bargaining, not a sudden, high-pressure demand.

- Allow Ample Time for Review: Never rush someone into signing. Always give the other party plenty of time to read the contract thoroughly and, most importantly, seek their own legal advice. Documenting that you made this offer is a huge point in your favor.

- Document All Contract Modifications: If the terms change during negotiations, write down why they changed and confirm that both sides agreed to the new terms freely.

Key Takeaway: A well-documented negotiation process is your best defense. It transforms a potential accusation of coercion into a clear story of voluntary, arm's-length bargaining between two informed parties.

Steps To Take if You Suspect Duress

What if you're on the receiving end of what feels like illegitimate pressure? How you react in the moment is critical. As we've covered, dragging your feet can be seen as accepting the contract, which could mean you lose your right to claim duress later on.

If you feel like you're being coerced, here's what to do:

- Protest Formally and in Writing: Don't just say it—write it. Send an email or formal letter as soon as possible stating that you are signing the agreement "under protest" or "under duress." This creates immediate, time-stamped evidence of your objection.

- Seek Immediate Legal Counsel: Do not wait. A lawyer can quickly tell you if the pressure you're facing legally qualifies as duress and map out the best way to protect your rights.

- Avoid Performing Under the Contract: If you can, hold off on acting on the contract's terms—don't make the payment, don't accept the delivery. Following through on your obligations can seriously weaken your claim because it suggests you've accepted the agreement.

In the end, it all comes down to robust documentation and taking swift, decisive action. Making these practices a core part of your operations is a cornerstone of any solid approach to holistic contract risk management, protecting your business and ensuring your agreements stand on a firm foundation of true consent.

Frequently Asked Questions About Contract Duress

When you get down to brass tacks, the idea of duress in contract law can bring up some tricky "what if" scenarios. Let's walk through a few common questions to see how these principles play out in the real world.

Is a Threat to Not Do Business Again Considered Duress?

Usually, no. A threat to stop doing business in the future is almost always seen as legitimate commercial pressure, not illegal duress. Think of it as hardball negotiation. If a supplier tells you, "Agree to our new pricing, or we won't renew your contract next year," that's just business.

Courts give companies a lot of leeway to decide who they want to work with. The line gets crossed when a threat involves an illegitimate action. For example, threatening to breach an existing contract unless you agree to new terms—that's a different story and could definitely be duress.

Can Signing a Prenup Just Before a Wedding Be Duress?

It absolutely can be, but the timing alone isn't a smoking gun. What courts look for is the bigger picture. Handing someone a prenuptial agreement a few days before the wedding can create a huge amount of emotional and psychological pressure, which might be enough to get it thrown out.

For a duress claim to stick, the person signing has to prove they were essentially forced into it against their will.

The real question is whether they felt they had any other reasonable choice. If they can show that the last-minute timing, combined with other pressures, left them feeling trapped with no way out, a court is much more likely to agree that duress was at play.

What Is the Difference Between Duress and Undue Influence?

This is a great question because they both involve improper pressure that can invalidate a contract. The key difference is in how that pressure is applied.

- Duress: This is about coercion, plain and simple. It's an overt threat or a wrongful act. Think of it as a "gun to the head" situation, whether that threat is physical, economic, or otherwise. The message is: "Sign this, or else."

- Undue Influence: This is far more subtle. It's about manipulation, not threats. It happens when one person uses a position of trust or authority to exploit another's vulnerability and improperly persuade them into a decision. You often see this in relationships with a clear power imbalance, like between an elderly person and a caregiver.

So, you can think of it this way: duress is a demand backed by a threat, while undue influence is a betrayal of trust that clouds someone's judgment.

Navigating contracts can feel like walking through a minefield of confusing terms and hidden risks. Legal Document Simplifier uses AI to instantly translate dense legal jargon into plain English, highlighting key obligations, deadlines, and potential risks. Protect your business and make smarter decisions by understanding every contract you sign. Get your clear, AI-powered contract summary today.