In contract law, consideration is the secret sauce that makes an agreement legally binding. It's the "this for that"—the value each person brings to the table. Think of it as the price paid for a promise.

Without this mutual exchange, you don't really have a contract. You just have a one-sided promise, which usually isn't something a court can enforce.

What Is Consideration in a Contract?

At its heart, consideration is what separates a professional, enforceable deal from a casual promise or a simple gift. It’s the core ingredient that proves both sides intended to create a real agreement.

This whole idea hinges on a concept called a "bargained-for exchange." This just means one person's promise has to actually motivate the other person's action or promise, and vice versa. It’s a deliberate trade, not just a happy accident where both parties happen to benefit.

This requirement ensures everyone has some skin in the game, making it clear they intend to be legally bound. To dive deeper, our full guide breaks down the https://legaldocumentsimplifier.com/blog/contract-law-definition-of-consideration in more detail.

The Value Component of Consideration

When lawyers talk about "value," they don't just mean cash. Consideration can be almost anything, as long as it has some legal worth.

A few examples include:

- An action: Agreeing to do something, like mow someone's lawn.

- A forbearance: Agreeing not to do something you have a right to do, like suing over a legitimate claim.

- Property: Transferring ownership of something, like a car or a house.

- A return promise: Promising to do something for the other party in the future.

The big idea here is that consideration has to be more than just a feeling of goodwill or a moral duty. It must be a real benefit to the person receiving it or a tangible detriment to the person giving it.

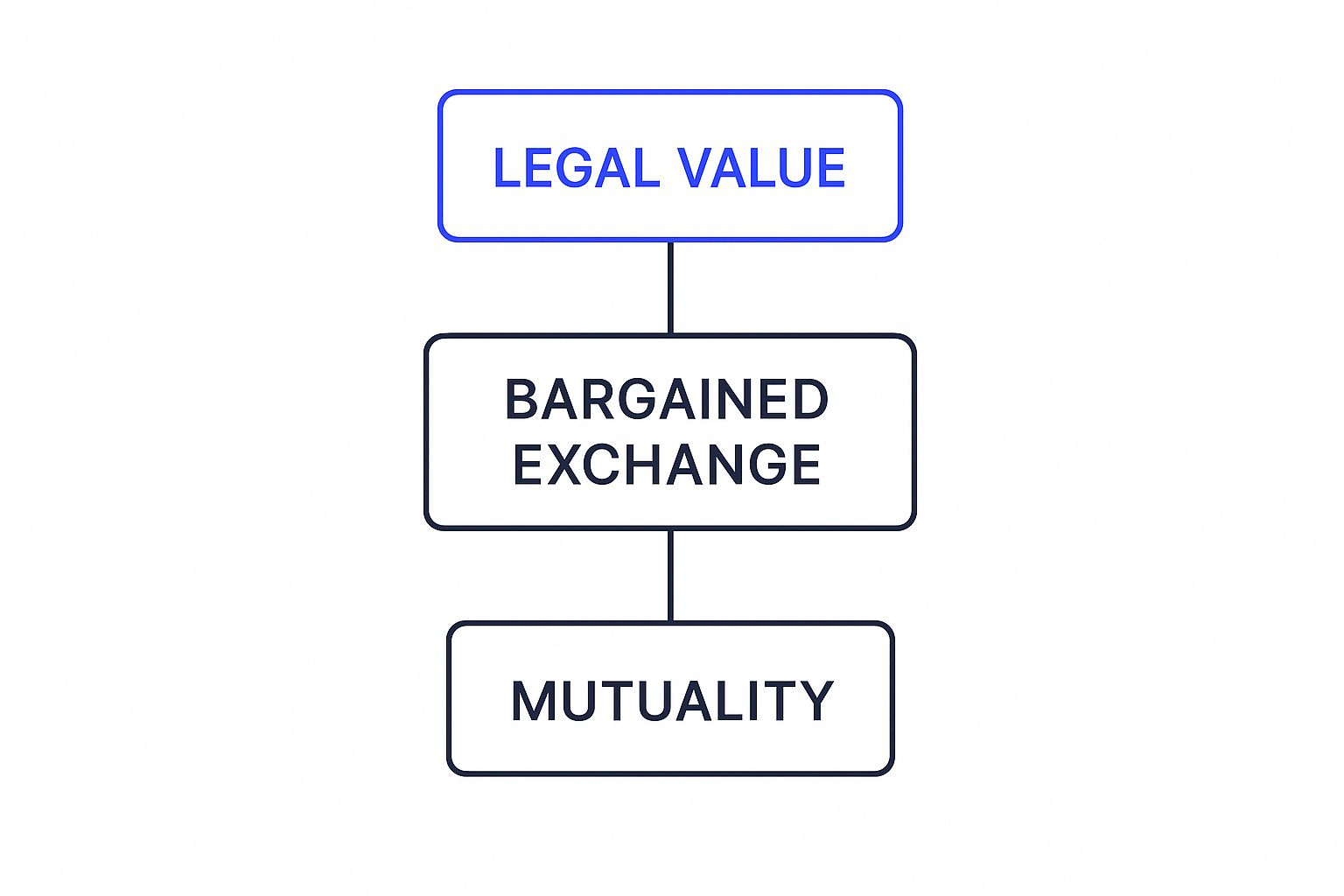

To help you see how these pieces fit together, here's a quick breakdown of what makes consideration legally valid.

Core Components of Legal Consideration

This table gives a quick overview of the essential parts that make consideration valid in a legally binding contract.

| Component | What It Means | Simple Example |

|---|---|---|

| Bargained-For Exchange | Both parties agreed to the exchange; it wasn't a gift or an accident. | You agree to pay a painter $1,000 because they agree to paint your house. |

| Legal Value | The "thing" being exchanged has recognizable worth under the law. | The $1,000 has monetary value, and the painting service has commercial value. |

| Mutual Obligation | Both parties are bound to do something (or not do something). | You are obligated to pay; the painter is obligated to paint. |

Understanding these components is fundamental to grasping all contract formation principles in business law.

Ultimately, consideration serves as tangible proof that a real bargain was struck. If it’s missing, a court will likely see the deal as a non-binding, generous promise and refuse to enforce it, leaving you without legal options if the other person backs out.

The Pillars of Valid Consideration

For a promise to actually become a legally binding contract, it needs what the law calls "valid consideration." Think of it like a three-legged stool—if any one of the legs is missing, the whole thing topples over. The agreement simply won't stand up in court.

These three essential "legs" are the benefit-detriment rule, the need for a bargained-for exchange, and the presence of legal value. Getting a handle on how each of these works is the key to understanding what makes a contract enforceable. Let's break them down one by one.

The Benefit-Detriment Concept

First up is the benefit-detriment concept. At its core, this idea says that for consideration to be valid, one party has to gain something they weren't already entitled to (a benefit), or the other party has to give up something they had a legal right to keep (a detriment).

It's really two sides of the same coin. The "benefit" is the advantage the person making the promise gets, while the "detriment" is what the person on the receiving end of the promise gives up. This doesn't have to be a huge sacrifice—it just has to be the surrender of a legal right.

For example, imagine your neighbor offers you $100 to promise you won't paint your house a wild shade of purple. In that deal, you're taking on a legal detriment because you're giving up your right to choose your home's color freely. At the same time, your neighbor gets a benefit: they don't have to stare at a purple house. Both sides of the benefit-detriment test are satisfied.

As you can see, legal value forms the base. From there, it has to be part of a bargained exchange, which ultimately creates mutual obligations for everyone involved.

The Bargained-For Exchange

The second—and arguably most important—pillar is the bargained-for exchange. This is the "this for that" element of the deal. It means the promise and the consideration have to be the direct reason for one another, distinguishing a real contract from a simple gift.

The person making the promise (the promisor) has to make it in order to get something in return. And the person receiving the promise (the promisee) has to give their consideration in order to get that promise. It’s a deliberate trade, not just two people coincidentally doing nice things for each other.

A critical point here is that generosity or rewards for past actions don't count. If your boss promises you a bonus because you did a fantastic job last quarter, that's technically a gift for something already done. It's not a bargained-for exchange for future work, so it's not enforceable.

This is a foundational concept, and you can explore more examples that help to define contract consideration in our related guide. The exchange must be the very reason the agreement exists.

Legal Value

Finally, we have the third pillar: legal value. This is where people often get tripped up. Legal value does not mean the deal has to be fair or financially equal. The law just requires that the consideration has some kind of value in the eyes of the court.

Judges generally won't get involved in whether you struck a good bargain or a bad one. As long as what was exchanged has some recognizable legal worth, the requirement is usually met. This value can take a few different forms:

- An Act: Doing something, like mowing a lawn or building a website.

- A Forbearance: Agreeing not to do something you have a legal right to do, like refraining from filing a legitimate lawsuit.

- Property: Handing over something tangible, like a car or a laptop.

- A Return Promise: Making a commitment to do something in the future, like promising to deliver goods next week.

What matters is that the value is real, not illusory. A promise to do something impossible, like paying someone with "magic beans," has no legal value. But a promise to sell a luxury car for just $1? That's technically valid. The dollar has legal value, even if the deal itself seems completely lopsided.

Sufficient Versus Adequate Consideration

When you first start digging into the legal definition of consideration in contract law, it's easy to get tripped up by two words that sound the same but mean very different things: "sufficient" and "adequate." In everyday conversation, they're practically interchangeable. In a courtroom, they are worlds apart.

Getting this distinction right is crucial. It’s the key to understanding why some contracts that look completely one-sided are still legally binding. The core principle is this: for a contract to hold up, consideration must be sufficient, but it absolutely does not need to be adequate. This idea is the bedrock of free-market bargaining, allowing people to make their own deals—good or bad.

The Standard of Sufficient Consideration

So, what does "sufficient" actually mean here? It simply means that whatever is being exchanged must have some value in the eyes of the law. It doesn't have to be much. It just has to be real and tangible.

This is where the famous "peppercorn theory" comes in. The idea is that if someone agrees to sell a massive estate for a single peppercorn, the contract is still valid. Why? Because the peppercorn, while obviously not a fair price, has a recognizable, physical value. It's not just an empty promise.

This isn’t just an old, dusty legal theory; it serves a practical purpose. Requiring sufficient consideration provides objective proof that both parties intended to make a real bargain, separating enforceable agreements from casual promises or gifts. It forces each side to give something up, which formalizes their intent and weeds out rash commitments. You can discover more insights about the general perspectives on consideration and see why this concept has stuck around for centuries.

Why Courts Avoid Judging Adequacy

While consideration needs to be sufficient, courts almost never step in to judge its adequacy. Adequacy is all about the fairness of the deal. Was the price fair? Did one person get a much better bargain than the other?

The legal system is built on the idea that adults are capable of looking out for their own interests and negotiating their own deals. If courts started voiding contracts just because they seemed unfair, it would open the floodgates to endless lawsuits and create chaos in the business world.

It's not a court's job to save people from making bad bargains. Their role is to confirm that a legally recognized exchange happened, not to second-guess the wisdom of that exchange. A promise to sell a brand-new car for $100 is, in almost all scenarios, an enforceable contract. The $100 is laughably inadequate, but it's still sufficient legal consideration.

Exceptions to the Rule

Of course, there are limits. While courts won't throw out a contract just because the price is low, a ridiculously one-sided deal can be a massive red flag. It can be used as evidence pointing to bigger problems with how the contract was formed, such as:

- Fraud or Misrepresentation: One party was lied to or tricked about the value of what they were getting.

- Duress or Undue Influence: Someone was threatened or improperly pressured into signing the agreement.

- Unconscionability: The deal is so incredibly lopsided that it "shocks the conscience" of the court.

In these cases, the inadequate price isn't the direct reason for voiding the contract. Instead, it’s the clue that leads the court to uncover the real issue—the fraud, the coercion, or the shocking unfairness. The contract fails because of the misconduct behind it, not because the deal itself was a bad one. This clever distinction protects people from being exploited while still preserving the freedom to make our own agreements.

Promises That Don't Count as Consideration

While it’s vital to know what makes consideration valid, it's just as important to recognize what doesn't make the cut. The law is surprisingly specific here, and a lot of promises that seem fair on the surface simply don't hold up in court. When a promise fails this test, the entire contract can become unenforceable, leaving everyone involved without legal protection.

Some types of promises are notorious for creating these kinds of "empty" agreements. We're talking about promises made for things you've already done (past consideration), promises to do something you were already supposed to do anyway (pre-existing duty), and promises so vague they don't actually commit you to anything (illusory promises).

Knowing how to spot these is key to drafting agreements that actually work.

The Problem with Past Consideration

Imagine you help your neighbor move a giant, heavy sofa on a Saturday afternoon. A week later, feeling grateful, your neighbor says, "You know, thanks again for your help last week. I'm going to give you $100 for your trouble."

If they never pay up, can you take them to court? Almost certainly not.

This is a classic example of past consideration. The act of helping—the supposed "consideration"—happened before the promise to pay was ever on the table. Because the payment wasn't part of a bargained-for exchange from the start, the law sees the promise of $100 as a nice gesture or a gift, not a legally binding contract.

A core tenet of contract law is that consideration must be part of the bargain. It has to be exchanged for the promise, not given as a reward for something that's already done and dusted. The timing is everything.

This rule exists to stop people from being legally trapped by simple expressions of gratitude. A promise to reward a past kindness might be the right thing to do morally, but it's missing the two-way street exchange needed to form a real contract. To dig deeper into this, you can read our full article on what is a consideration and why its timing is so crucial.

The Pre-Existing Duty Rule

Another common pitfall is the pre-existing duty rule. In simple terms, this rule says that promising to do something you're already legally obligated to do isn't fresh consideration. It's designed to prevent one party from holding the other over a barrel to get more money for the exact same work.

Let’s say a contractor agrees to build a deck for you for $5,000. Halfway through the project, they down tools and demand an extra $1,000 to finish the job on schedule. Even if you reluctantly agree just to get it done, that new promise probably isn't enforceable. Why? Because the contractor already had a pre-existing duty to build the deck for the original $5,000.

Of course, there are important exceptions. If the original deal is modified to include new responsibilities, then fresh consideration has been created.

- Adding New Work: If you ask the contractor to add built-in benches that weren't in the original plan, your promise to pay more is valid because they are taking on new duties.

- Unforeseen Difficulties: If the contractor hits a massive, unexpected boulder underground that requires special equipment to remove, a promise to pay more for that extra, unforeseen work would likely be enforceable.

These principles have deep roots in legal traditions from around the world. For instance, English contract law, which heavily influences U.S. law, established long ago that performing a pre-existing duty doesn't count as new consideration unless you're providing something extra. This idea is also found in legal systems like the Indian Contract Act of 1872, which governs agreements for over a billion people and requires that both parties get something of value in return.

Illusory Promises

Finally, we have promises that are so vague or non-committal that they don't actually count as valid consideration. These are called illusory promises because they create the illusion of a commitment without actually binding the person to do anything at all.

Think of a business owner telling an employee, "If you do a great job this year, I might give you a share of the profits." The words "might" and "a share" are so indefinite that they create no real obligation. The owner has complete discretion and hasn't actually promised anything specific.

Other examples of illusory promises include:

- A promise to buy a product "if I feel like it."

- An agreement where one party can cancel "at any time, for any reason, without notice."

For a promise to serve as valid consideration, it needs to be definite enough for a court to enforce. Without a clear commitment, there’s no real exchange of value, and therefore, no contract.

When Can You Enforce a Promise Without Consideration?

While the whole "bargained-for exchange" idea is the heart of most contracts, the law isn't a robot. Courts know that sometimes, sticking rigidly to the consideration rule would lead to a seriously unfair result. To stop that from happening, the legal system has carved out a few key exceptions where a promise can be enforced even if there isn't a traditional two-way street of value.

These aren't just loopholes for casual promises you might make to a friend. They are specific legal tools used carefully when one person's promise has pushed another to take a major step. The most important of these is promissory estoppel, a principle that can make a one-sided promise legally binding.

What Is Promissory Estoppel?

Think of promissory estoppel as a legal safety net. It stops a person from backing out of a promise when someone else reasonably relied on it and would be harmed if the promise were broken. It catches the person who trusted the promise, preventing them from suffering a big loss just because the other party had a change of heart.

For this to kick in, a court usually needs to see four things:

- A Clear Promise: One party had to have made a clear and definite promise to the other.

- Reasonable Reliance: The person who heard the promise must have reasonably trusted it. Their belief that it would be kept has to be justifiable.

- Real Harm: Because they trusted the promise, the person took a significant action that left them in a worse spot—often costing them time, money, or a major life change.

- Injustice: The only way to avoid a serious injustice is to enforce the promise.

This doctrine isn’t about making every casual promise legally binding. It’s about fixing a situation where one person's words directly caused someone else to suffer a real, tangible loss.

A Real-World Look at Promissory Estoppel

Let's see how this plays out with a classic job offer scenario. Imagine a company in San Francisco offers a dream job to Alex, a talented designer living in New York. The offer is clear, exciting, and seems like a sure thing.

- The Promise: The company promises Alex a specific salary, a start date, and a key role in a new project.

- The Reliance: Trusting this promise completely, Alex quits their steady job in New York.

- The Detriment: Alex then sells their apartment, hires movers, and relocates their entire family across the country, spending thousands of dollars in the process.

- The Reversal: A week before Alex is supposed to start, the company calls and pulls the offer, blaming an internal budget cut.

Here, there's no formal employment contract, so there’s no consideration. Alex hadn't worked a single day, so they hadn't given the company anything of value in exchange for the salary.

But a court would likely use promissory estoppel here. Why? Because letting the company walk away would be a massive injustice. Alex’s reliance was reasonable, and their actions led to huge financial and personal losses. The court could order the company to pay for Alex's moving costs, lost wages, and other related damages.

Key Takeaway: Promissory estoppel is the law’s way of saying you can't make a serious promise, watch someone act on it to their detriment, and then just say, "Never mind."

Other Important Exceptions

While promissory estoppel gets most of the attention, a couple of other situations can make a promise enforceable without any new consideration.

- Promises to Pay Old Debts: Let's say someone owes a debt that's so old the legal time limit to collect it (the statute of limitations) has run out. They are no longer legally required to pay. But if that person makes a new promise to pay back the old debt, that new promise is typically enforceable, even without any new exchange.

- Charitable Pledges: When someone pledges a donation to a charity, and the charity relies on that money to move forward with a project—like starting construction on a new hospital wing—courts may enforce the pledge. Doing so prevents the charity from being harmed after it relied on the promised funds in good faith.

How Consideration Evolved Through History

To really get a feel for what consideration means in modern contract law, it helps to rewind the clock. This isn't some concept that lawyers dreamed up overnight. It's a doctrine that has been shaped and refined over centuries, adapting to the ever-changing world of business and society.

The journey started in medieval England, where making a promise legally binding often had very little to do with a fair exchange. It was all about formality. If you wrote down a promise and stamped it with a wax seal, that was pretty much it—you had a binding deed. It didn’t matter if the other person gave you anything in return. The seal was the magic ingredient, proof that you were serious.

From Formal Seals to Fair Bargains

As commerce started to get more complicated, the old seal-based system just couldn't keep up. The courts needed a better, more flexible way to tell the difference between a serious, two-sided bargain and a casual, one-off promise.

This forced a huge shift in legal thinking. Slowly but surely, the focus moved away from the formal seal and toward the actual substance of the deal. Enforcing a promise became less about fancy documents and more about whether both sides were giving something up. This was a critical move from a rigid, check-the-box approach to a model focused on making sure agreements were fair and reciprocal. If you want to dive deeper into this evolution, Pax Law's website has a great breakdown of how English common law shaped the principle.

This whole process laid the foundation for the modern idea of a bargained-for exchange, which is now the absolute core of contract law.

The Rise of the Benefit-Detriment Test

The biggest leap forward came in the 16th and 17th centuries with the invention of the "benefit-detriment" test. This was a game-changing idea that completely redefined how courts looked at agreements.

The concept was simple but powerful: a promise is only enforceable if one party gets a real benefit they weren't already entitled to, or the other party suffers a real detriment by giving up something they had a legal right to keep.

This test gave courts a clear, logical framework. It forced them to analyze the substance of a deal—what was each person actually giving and getting?—instead of just looking for a wax stamp. It was the first real attempt to put into law the simple idea that a contract has to be a two-way street.

This historical journey shows that consideration isn't just some random legal hurdle. It’s a fundamental principle born from centuries of experience, designed to bring fairness and predictability to every deal.

Common Questions About Consideration in Contracts

Even when you've got a handle on the basics, the legal definition of consideration in contract law tends to raise some tricky questions. It's an area full of nuances that can easily trip people up.

Let's clear the air and tackle a few of the most common questions with practical, no-nonsense answers. These scenarios pop up all the time in business and personal agreements, so getting the details right is the difference between a solid contract and a promise that won't hold up in court.

Can a Promise to Give a Gift Be Legally Enforced?

Usually, the answer is no. A promise to give a gift is what lawyers call a "gratuitous promise" because it’s a one-way street—it completely lacks consideration.

The person receiving the gift isn't giving anything of legal value in return, so there's no bargained-for exchange.

But there's a big exception. If the person who was promised the gift reasonably relies on that promise and suffers a financial loss because of it, the situation changes.

Imagine a friend promises to give you a car for your new delivery business. Relying on that, you sign a non-refundable lease for a commercial garage. If your friend backs out, a court might step in. Under a principle called promissory estoppel, the promise could be enforced to prevent a seriously unfair outcome.

What Is the Difference Between Consideration and Subject Matter?

This is a frequent point of confusion, but the distinction is actually pretty simple once you see it.

Think of it like this:

- Subject Matter: This is the "what" of the contract. It’s the specific thing being exchanged, like a car, a house, or a web design service.

- Consideration: This is the "why" of the contract. It's the value each side agrees to give up to make the deal binding. It’s the money for the house or the promise to design the website.

In a deal to sell a car, the car is the subject matter. The consideration is the buyer's promise to pay $10,000 in exchange for the seller's promise to hand over the keys and title. The two are deeply connected, but they are different legal concepts.

Does Consideration Have to Be Money?

Not at all. While cash is the most common form, legal consideration can be almost anything of value. The law is incredibly flexible on this point, as long as what's being exchanged has some recognizable worth and was part of a real bargain.

This flexibility is what allows contracts to cover such a huge range of agreements. Other valid forms of consideration include things like:

- A promise to do something (like painting a neighbor's fence).

- A promise not to do something (like agreeing not to sue someone).

- An exchange of goods or property (trading your old laptop for a new bike).

- Providing a service (offering marketing advice in exchange for accounting help).

The only thing that matters is that the exchange has some value recognized by law and both sides agreed to it.

Navigating the complexities of legal documents can be daunting. Legal Document Simplifier uses AI to instantly translate dense contracts, leases, and agreements into clear, simple summaries. Upload your document today and get the clarity you need to make confident decisions. Visit Legal Document Simplifier to get started.