In the legal world, to quash something means to officially cancel or void a court's directive, like a subpoena or a search warrant. It essentially hits the undo button, erasing the order's legal authority.

Think of it like a movie director yelling "cut!" and deciding a scene doesn't work. The scene is scrapped from the final film as if it never existed. That’s the core idea behind what it means to quash something in court—the legal action is invalidated.

Understanding the Power to Quash in Court

At its heart, the court's power to quash a legal action is a fundamental check within our justice system. This isn't just about fixing a typo or a minor administrative error; it's a powerful tool that upholds due process and protects people from unfair, improper, or ridiculously burdensome legal demands. It ensures the entire process stays fair from the get-go.

The concept is anything but new. The word "quash" has deep roots in history, first popping up around 1275. By the 18th century, it had a firm legal meaning: "to suppress or put down; to undo or destroy in a complete or summary manner." This evolution from physical force to judicial power shows just how much our legal language has adapted alongside our ideas of justice. You can discover more on the etymology of great legal words and their journey through time.

Why Quashing an Order Is So Important

So, why is this corrective tool so critical? Quashing serves several vital functions that maintain the integrity of legal proceedings. It’s a necessary check on power, making sure legal tools are issued and used the right way.

Here are the main reasons a party might file a motion to quash:

- Preventing Abuse of Process: It stops one side from weaponizing legal tools, like using a subpoena simply to harass an opponent or go on a "fishing expedition" for irrelevant information.

- Protecting Privileged Information: It safeguards legally protected communications from being wrongfully exposed, like conversations between a lawyer and their client or a doctor and their patient.

- Avoiding Undue Burden: It shields individuals and companies from demands that are excessively expensive, time-consuming, or disruptive, especially if the information sought has little relevance to the actual case.

A wide variety of legal actions can be challenged with a motion to quash. The table below summarizes some of the most common examples.

Common Legal Actions That Can Be Quashed

| Legal Action | Reason for Quashing |

|---|---|

| Subpoena | Improperly served, demands privileged information, or is overly broad and burdensome. |

| Arrest Warrant | Issued without probable cause or based on false information provided in the affidavit. |

| Search Warrant | Lacks specificity about the place to be searched or items to be seized. |

| Indictment | Grand jury proceedings were flawed, or there was insufficient evidence presented. |

| Service of Process | The summons and complaint were not delivered to the defendant correctly. |

As you can see, the reasons often boil down to procedural errors, a lack of proper legal foundation, or a violation of someone's rights.

A court's decision to quash an order is a powerful declaration that the legal system’s own rules must be followed. It reinforces the principle that no legal command is absolute and must stand up to scrutiny.

Ultimately, quashing isn't about letting someone off the hook or helping them evade responsibility. It’s about ensuring that any legal demand made upon a person is valid, reasonable, and lawful.

How a Motion to Quash Works in Practice

So, how does the abstract idea of tossing out a legal order actually play out in the real world? It all comes down to a specific legal tool called a motion to quash. This isn't some dramatic courtroom outburst you see in the movies; it’s a formal, written request submitted to a judge asking them to invalidate an order.

Think of it as raising a formal objection before the game even starts. The goal of a motion to quash is to challenge a legal command—like a subpoena or a warrant—before you have to obey it, by arguing that it's fundamentally flawed in some way.

Filing this motion is a proactive step. Instead of just rolling over and complying with an improper order, a person can ask the court to step in and nullify it, essentially erasing its legal power right from the get-go.

The Steps in the Motion Process

So, who can actually file this request? It's usually the person directly targeted by the order, like an individual who gets a subpoena to testify. But it’s not just them. A third party with a direct interest in the case, like a company whose confidential records are being demanded from a former employee, can also file a motion to quash to protect their information.

The process itself is pretty structured and generally follows these key steps:

- Drafting the Motion: A lawyer puts together a formal written document that clearly states the request to quash the order.

- Stating the Grounds: This is the most critical part. The motion must lay out the specific legal reasons why the order is invalid. This could be anything from improper service (it wasn't delivered correctly) to requesting privileged information.

- Filing and Serving: The motion is officially filed with the court clerk, and a copy is delivered to the opposing party who issued the original order.

- The Hearing: The judge often schedules a hearing where lawyers for both sides can argue their points before a decision is made.

This formal procedure is a cornerstone of due process. In modern legal systems, especially in the U.S., the term 'quash' isn't just a fancy word; it's a procedural tool used to cancel prior actions. In fact, U.S. federal courts see hundreds of motions to quash filed every year to fix procedural mistakes or challenge jurisdiction, all following a specific set of rules. You can dive deeper into the procedural rules for quashing legal demands to see just how this system is designed to work.

A motion to quash is what turns a legal principle into a tangible action. It’s the practical mechanism that allows people to defend their rights against legal commands that may be flawed or simply go too far.

Common Reasons to Quash a Subpoena

Getting hit with a subpoena can feel like an order you simply can't refuse, but that’s not always the final word. A court will agree to quash a subpoena—essentially, to cancel it—if the person challenging it has a solid legal reason. These aren't just convenient loopholes; they're established rules designed to keep the legal process fair and lawful for everyone involved.

So, what are these reasons? Most fall into a few key categories. Understanding them gives you a practical sense of what it takes to get a subpoena thrown out.

Procedural and Service Errors

The law is surprisingly specific about how a subpoena must be delivered, or "served." If the party that issued it messes up this process—say, by leaving it with someone who isn't authorized to accept it or by not delivering it within a required timeframe—the subpoena can be quashed. It's a fundamental rule that ensures everyone gets proper, fair notice.

A subpoena might also get tossed if it comes from a court that doesn't have jurisdiction over you or the information it's asking for. Think of it as a jurisdictional check to prevent legal overreach.

Requests for Privileged Information

Some conversations are legally protected to promote total honesty and trust. A motion to quash is a common tool used to shield this privileged information from being exposed.

Here are a few classic examples:

- Attorney-Client Privilege: This protects confidential talks between a client and their lawyer when seeking legal advice.

- Doctor-Patient Confidentiality: Your private medical records and conversations with a doctor are off-limits.

- Spousal Privilege: Communications between a married couple are often protected from being revealed in court.

A subpoena can't be used as a crowbar to break these legally recognized shields. Quashing it is how the courts enforce these critical privacy rights.

Creates an Undue Burden

Perhaps the most common reason a subpoena gets quashed is that it creates an undue burden. This is legal-speak for a request that is way too difficult, expensive, or time-consuming to be considered reasonable, especially when weighed against how important the information is to the case.

For example, imagine a small business getting a demand to produce ten years of financial records for a minor dispute it has almost nothing to do with. That would almost certainly be seen as an undue burden. It's important to distinguish this from feeling pressured into an agreement, a topic you can learn more about by reading our guide on duress in contracts.

Ultimately, the court has to balance the value of the information against the effort needed to dig it up. It's all about keeping legal demands reasonable.

Quashing Indictments and Other Court Orders

The ability to quash a legal document isn't just for routine paperwork like subpoenas. It’s a powerful tool that can challenge the most serious actions in our justice system, from grand jury indictments to arrest warrants. Think of it as a vital check on authority.

The ability to quash a legal document isn't just for routine paperwork like subpoenas. It’s a powerful tool that can challenge the most serious actions in our justice system, from grand jury indictments to arrest warrants. Think of it as a vital check on authority.

Imagine a prosecutor gets a grand jury to indict someone. If the defense team can show that the indictment was based on flimsy evidence or that the prosecutor acted improperly, they can file a motion to quash it. It's a bold legal move that can stop a criminal case in its tracks before it even really gets started.

Challenging Warrants and Indictments

Getting these high-stakes orders thrown out is no small feat. You have to prove there was a fundamental flaw in how they were issued. The bar is high because these orders are meant to be based on a solid finding of probable cause.

So, what kind of serious problems could justify quashing an indictment or warrant? Here are a few examples:

- Prosecutorial Misconduct: This might happen if a prosecutor knowingly uses false testimony to sway a grand jury or conveniently forgets to present evidence that would clear the person being investigated.

- Lack of Sufficient Evidence: A judge could quash an indictment if the evidence presented was so weak that no reasonable person would have found probable cause for the charges.

- False Information in an Affidavit: If a police officer intentionally or recklessly lies in a sworn statement to obtain a search warrant, a defense attorney has grounds to challenge it.

If you want to go deeper on this, you can learn more about what it means when a warrant is quashed and the legal steps involved. This kind of challenge, often called a Franks motion, is specifically designed to attack the truthfulness of the information used to get the warrant in the first place.

To quash an indictment or warrant is to strike at the very foundation of a legal case. It asserts that the process was so deeply flawed that any action resulting from it is legally void.

This power ensures that even the most serious legal actions must follow strict constitutional rules. By allowing these orders to be challenged and potentially thrown out, the system provides a crucial safeguard against miscarriages of justice, making sure legal authority is used fairly and lawfully at every turn.

Quash vs. Dismiss vs. Overturn: What's the Real Difference?

In the legal world, some words seem to mean the same thing but carry entirely different legal weight. Quash, dismiss, and overturn all signal that a legal action has stopped, but they aren’t interchangeable. Getting the distinctions right is crucial to understanding what’s actually happening in a case.

Let's use a quick sports analogy to clear things up:

- To quash an order is like a referee blowing the whistle on a single, illegal play. That specific action is wiped off the board as if it never happened, but the game itself keeps going.

- To dismiss a case is like the referee calling off the entire game before the final whistle, usually because of a fundamental problem that prevents one team from competing fairly.

- To overturn a verdict is more like the league headquarters reviewing the game tape later and reversing the final score. This is an appellate decision that happens long after the original game is over.

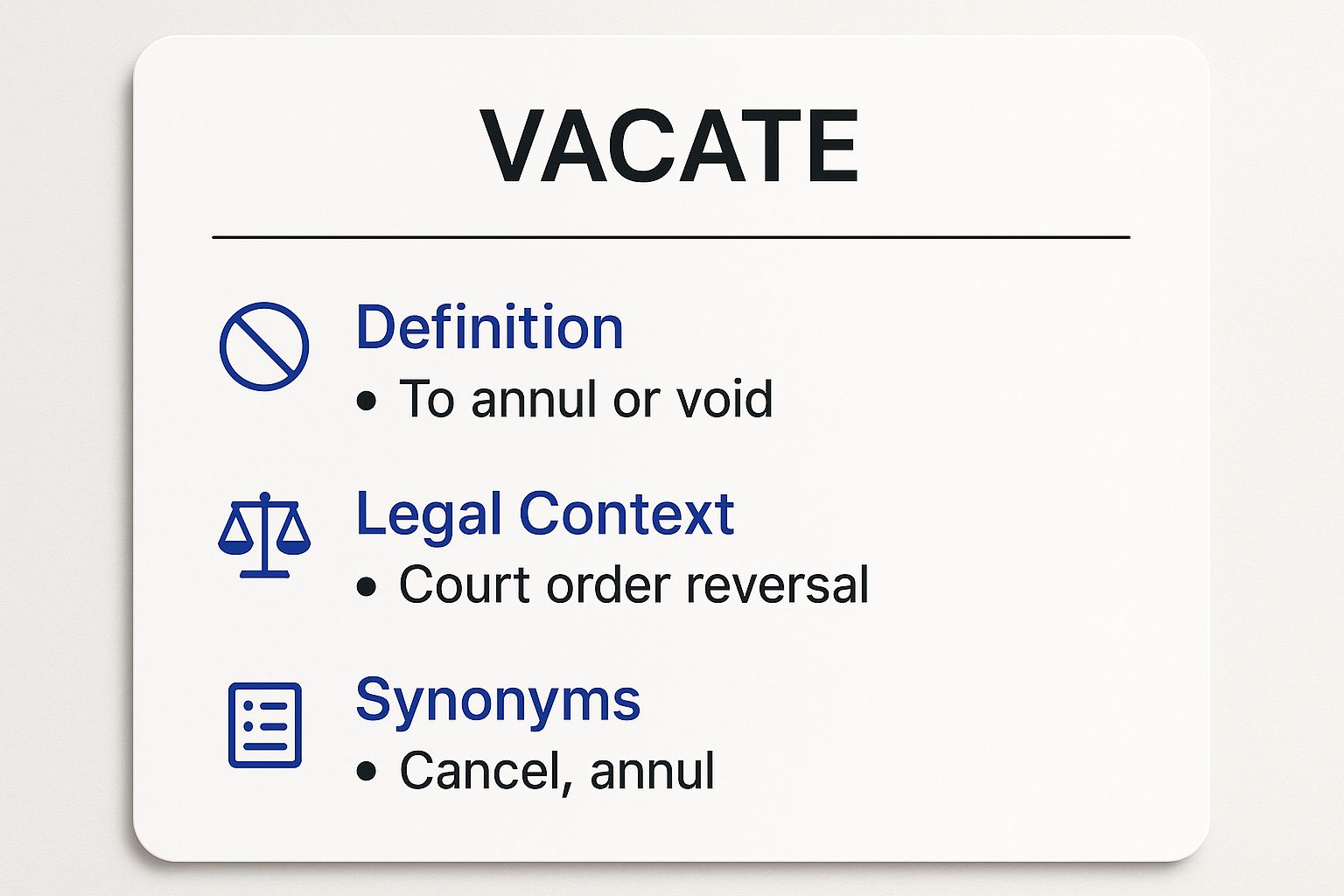

This visual helps break down what it means to quash something in a legal setting.

As you can see, quashing is a targeted action that voids a specific legal instrument, like a subpoena or a warrant, without necessarily ending the entire case.

Comparing Key Legal Actions: Quash vs. Dismiss vs. Overturn

Let's put these terms side-by-side to highlight their unique roles. Each one applies at a different stage of the legal process, is carried out by a different level of the court, and has a very different impact on the case as a whole. Knowing these distinctions helps you make sense of court rulings and the power of legal precedent. To learn more, you can explore our guide on what does precedent mean and see how it influences legal outcomes.

The table below breaks down the key differences between these three important legal actions.

| Term | What It Affects | Who Takes the Action | When It Happens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quash | A specific order or action (e.g., subpoena, warrant). | A trial court judge. | Before or during a case, often at a preliminary stage. |

| Dismiss | The entire lawsuit or criminal case. | A trial court judge. | During the pre-trial phase or even during the trial itself. |

| Overturn | The final verdict or judgment of a lower court. | An appellate court (a higher court). | After a case has concluded and been appealed. |

So, to wrap it up: quashing is a precise strike against one part of a case. A dismissal brings the entire proceeding to a halt at the trial level. And an overturn is a reversal of a final decision, handed down from a higher court on appeal. Each term tells a very different story about the legal journey of a case.

Of course. Here is the rewritten section, designed to sound like it was written by an experienced human expert, following all your specified requirements.

Your Questions About Quashing Answered

Even after getting a handle on the definition, you're bound to have some practical questions about what it means to quash something in the real world. Let's walk through a few common scenarios to make sure the concept is crystal clear.

So, what happens if your motion to quash is successful? In short, the legal order you were challenging—whether it was a subpoena, a warrant, or something else—is officially canceled. It’s now legally void and unenforceable, almost as if it never existed. You are no longer required to follow its instructions.

Keep in mind, though, that this doesn't necessarily kill the underlying legal case. The other party might just go back to the drawing board, fix whatever was wrong with the first order, and issue a new one that stands up to legal scrutiny.

Can a Decision to Quash Be Appealed?

Yes, absolutely. A judge's ruling on a motion to quash isn't always the final word. If a judge agrees to quash an order, the party that issued it can take the matter to a higher court, arguing that the judge made a legal error. On the flip side, if the judge denies the motion, the person who filed it can often appeal that decision, too.

This appeals process acts as a crucial check and balance within the justice system. It’s there to ensure the trial court applied the law correctly and fairly.

The ability to challenge and appeal decisions related to quashing underscores a core principle of law: no single order or ruling is beyond scrutiny. The process is designed to be rigorous and fair at multiple levels.

Why You Need a Lawyer

Trying to file a motion to quash on your own is a bad idea. This isn't a DIY project. The legal system is a maze of complex procedural rules, tight deadlines, and subtle arguments that can make or break your case. An experienced lawyer knows how to spot valid reasons for quashing an order, draft a motion that gets a judge's attention, and argue your position effectively in court.

If you go it alone, you risk missing a critical deadline or making a weak argument, which could lead the court to uphold an order that was flawed from the start. When you're up against a legal command, professional legal advice is almost always essential to have any real chance of success.