Think of a contract as a handshake—a voluntary deal between two parties. Now, imagine someone twisting your arm behind your back and forcing you to shake on it. That’s the essence of duress in contract law. It’s when improper pressure or threats become so overwhelming that they rob you of your free will, pushing you to accept terms you’d normally walk away from.

Defining Duress in Contract Law

At its heart, a contract is a promise the law will stand behind. But for that promise to be solid, it has to be made freely. Duress shatters this core principle, turning what should be a willing agreement into an act of forced submission.

When duress is in play, the consent one party gives isn't genuine. The law sees this power imbalance and offers a way out. A contract signed under duress is considered voidable, not automatically void. This is a critical distinction—it puts the power back in the hands of the person who was coerced. They get to decide whether to cancel the contract or, if the threat is gone and the deal still works for them, to go ahead with it.

The Foundation of Genuine Consent

The whole idea of contract law is built on a "meeting of the minds," where both sides knowingly and willingly agree to the same thing. Without that genuine consent, the agreement just doesn't hold up. Duress completely undermines this by swapping free will for fear.

Here’s another way to look at it: tough negotiation is like a hard-fought game of chess. It’s competitive but fair. Duress, on the other hand, is like your opponent knocking the board over and forcing you to say they won. The first is just business; the second is coercion, and it invalidates the whole thing.

To successfully claim duress, you generally need to prove two things:

- Illegitimate Pressure: The threat used against you was wrongful or unlawful.

- Causation: That pressure was the main reason you signed the contract, leaving you with no other reasonable choice.

A contract tainted by duress is fundamentally flawed because one party's consent was obtained through coercion, not voluntary agreement. The law provides an exit ramp for the victim, allowing them to void the agreement and escape its obligations.

Why This Matters for You

Understanding duress isn't just for lawyers. Whether you're a business owner, a freelancer, or just someone signing an agreement, knowing how to spot coercion is a crucial skill. It’s what protects you from getting trapped in a bad deal you were pressured into. The legal terms can get tricky, but grasping these basics is the first step. If you're looking for more help on this, our guide to understanding legal jargon can help clear up some of the confusing terminology.

This guide will walk you through the different kinds of duress, how you can prove it, and what steps to take if you think you’ve been a victim.

The Three Main Forms of Duress

Duress in a contract isn't just one thing. Think of it as a spectrum of coercion, running from blatant physical threats all the way to subtle but crippling financial pressure. To really get a handle on it, you need to break it down into its three main forms. While each has its own unique flavor, they all boil down to the same problem—they destroy the genuine consent that holds up any valid agreement.

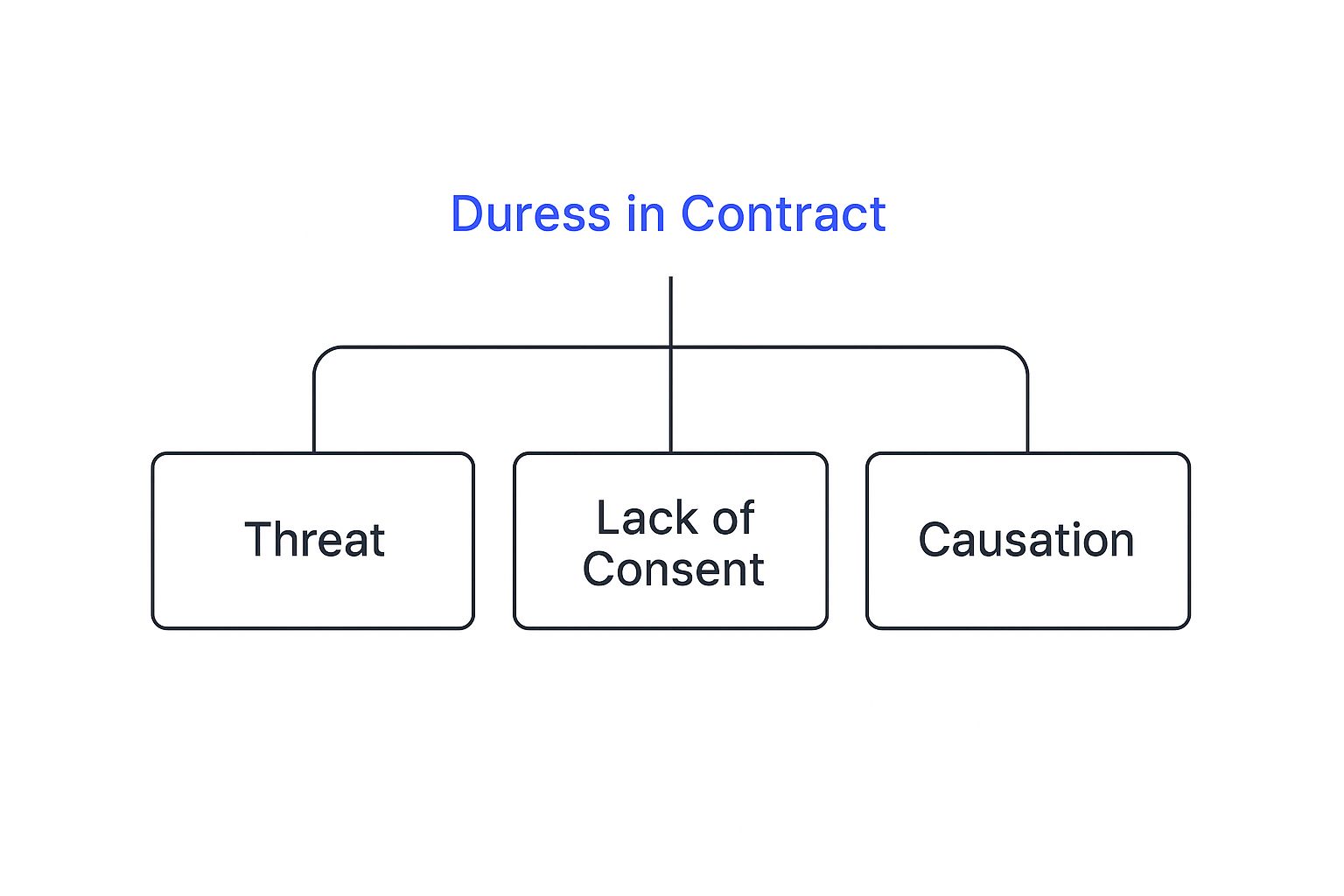

This simple hierarchy shows the core elements that build a duress claim, branching from the initial threat to its ultimate impact on consent and causation.

This visual underscores how a wrongful threat must directly lead to a lack of genuine consent for a duress claim to be valid, linking the action to the consequence.

Physical Duress: The Most Obvious Threat

This is the most straightforward and easiest type of duress in contract law to spot. It happens when someone signs a contract because they’re facing the threat of physical harm. The threat could be aimed at them, their family, or even a close friend.

It’s the classic "gun to the head" scenario. The threat doesn’t have to be deadly; any threat of violence or imprisonment serious enough to crush a person's free will counts.

For instance, if a business partner threatens to hurt you unless you sign over your company shares for pennies on the dollar, that contract was signed under physical duress. The agreement is voidable because your signature wasn't a choice—it was a reaction to fear.

Duress of Goods: Holding Property Hostage

A less violent but equally coercive tactic is duress of goods. This is when one party illegally holds, damages, or threatens to destroy someone else’s property to strong-arm them into a contract. The heart of the issue is the wrongful withholding of something that isn't theirs.

Imagine you take your prized vintage car to a mechanic for a simple tune-up. When you come back, the mechanic hits you with a surprise bill for $10,000 in unauthorized work and refuses to give you the keys until you agree to pay.

You need your car, so you sign the agreement through gritted teeth. This contract was formed under duress of goods. The mechanic used your property as leverage to force an unfair deal, making it legally voidable.

Economic Duress: The Modern Business Threat

Economic duress is the most common—and often trickiest—form of duress you’ll see in the business world. It’s when one party uses illegitimate economic pressure to force another into accepting terms they would never have agreed to otherwise.

This goes way beyond "hard bargaining" or the usual pressures of the marketplace. For it to count as economic duress, the pressure must be wrongful and leave the victim with no other realistic choice but to give in.

Illegitimate pressure is the key factor that distinguishes tough negotiation from unlawful economic duress. The threat must go beyond what is considered acceptable commercial practice, such as threatening to breach a contract in bad faith.

The concept of duress has come a long way since it was formally recognized in English common law back in the 19th century. The landmark case of Barton v Armstrong (1976) set a major precedent, establishing that a contract signed due to threats is voidable. This principle now covers everything from threats to life and safety to the kind of economic pressure that strips a party of their free will. You can explore more about these foundational legal doctrines and their history.

Consider this all-too-common scenario:

- A manufacturer relies on a sole supplier for a critical component and is facing a tight client deadline.

- Out of the blue, the supplier threatens to stop all shipments unless the manufacturer agrees to a 50% price hike and a new long-term contract with awful terms.

- If the manufacturer misses that shipment, they’ll default on their own contract, facing catastrophic financial losses and a ruined reputation.

With no other suppliers and no time to find one, the manufacturer signs. This is a textbook case of economic duress. The supplier used an illegitimate threat—breaching their current agreement—to exploit a vulnerability and force a new one.

What It Takes to Prove Duress in Court

Claiming you were forced into a contract is a serious allegation, but just feeling pressured isn’t enough for a court to step in. To successfully prove duress in contract law, you need to build a case that stands on two unshakable legal pillars: illegitimate pressure and causation.

Think of it like building an arch—both sides must be solid for it to hold up. If you can only show that you were under immense stress but the pressure wasn’t legally "wrongful," your claim will likely crumble. The responsibility to prove both elements rests squarely on your shoulders.

The First Pillar: Illegitimate Pressure

First and foremost, you have to demonstrate that the pressure was illegitimate. This is where courts draw the line between tough negotiation and unlawful coercion. A bad deal made under stress won’t cut it; the threat itself has to be wrongful.

So, what makes a threat illegitimate? It generally falls into one of three buckets:

- Unlawful Acts: This is the most straightforward category. Any threat to commit a crime or a tort (a civil wrong) is automatically illegitimate. Threatening physical harm or to destroy property fits perfectly here.

- Threats to Breach a Contract: Often seen in economic duress, threatening to violate an existing agreement to exploit someone's vulnerability is a big red flag. A classic example is a supplier threatening to halt a critical shipment unless you agree to a sudden price hike.

- Threats of Lawful Action in Bad Faith: Even a threat to do something perfectly legal can become illegitimate if it’s used for an improper purpose. Imagine threatening to report a minor regulatory slip-up—not to uphold the law, but purely to corner someone into signing a deal. That could be seen as illegitimate.

The Second Pillar: Causation

Once you've established illegitimate pressure, you must prove that it directly caused you to sign the contract. This is the causation element. Essentially, you need to show that the threat was so significant that it left you with no other reasonable choice.

A judge will ask a simple question: "If not for this threat, would you have signed?" If the answer is a clear "no," you're on the right track. The pressure had to be severe enough to overwhelm your free will. If you had other viable options—like finding another supplier quickly or seeking a swift legal remedy—it's much harder to argue you were truly coerced.

You can learn more about how these concepts intertwine by exploring the fundamentals of contract law duress at https://legaldocumentsimplifier.com/blog/contract-law-duress.

To prove a duress claim in court, you must demonstrate that both illegitimate pressure and causation were present. The following table breaks down what the court will look for when evaluating each element of your claim.

Core Elements of a Successful Duress Claim

| Element | Description | Key Question for the Court |

|---|---|---|

| Illegitimate Pressure | The threat or pressure applied must be unlawful or wrongful. This can include threats of violence, breach of contract, or abuse of legal process. | Was the pressure applied a violation of the law or so morally wrong that it justifies voiding the contract? |

| Causation | The illegitimate pressure must be the direct reason the person entered into the contract. Their free will was overcome by the threat. | Did the coerced party have any reasonable alternative but to agree to the terms? |

Without solid evidence for both of these pillars, even a contract that feels deeply unfair will likely be upheld.

To establish causation, the coerced party must demonstrate they had no practical alternative but to submit to the demand. The court looks for a clear link between the illegitimate threat and the act of signing the contract.

Gathering strong evidence is crucial. When doing so, it's important to understand how the legal discovery process might be affected by things like recorded virtual meetings. Your best asset is thorough documentation, including:

- Written Correspondence: Emails, text messages, and letters that contain the coercive threats.

- Witness Testimony: Statements from anyone who observed the behavior.

- Timeline of Events: A detailed log showing the timing of the pressure in relation to the contract signing.

- Financial Records: Documents that illustrate the economic vulnerability the other party exploited.

Ultimately, proving duress in a contract requires a methodical approach. You need to present clear, compelling evidence that turns a subjective feeling of pressure into an objective, legally sound case of coercion.

Seeing Duress in Action with Real-World Cases

Legal concepts can feel a bit abstract until you see them play out in a real situation. The best way to truly grasp duress in contract law is to move from theory to reality. By looking at actual court cases, we can see how judges dissect arguments, weigh the evidence, and ultimately decide when a contract crosses the line from a tough bargain into an unenforceable agreement.

These stories aren't just academic exercises—they are tangible examples of how illegitimate pressure can completely unravel a contract. Let's dive into a famous case of economic duress and contrast it with a more straightforward example of physical coercion to bring these principles to life.

The Shipbuilders and the Price Hike

One of the most-cited cases involving economic duress is North Ocean Shipping Co Ltd v Hyundai Construction Co Ltd. It’s a powerful illustration of how one party can weaponize a contract breach to force an unfair deal.

The story starts when North Ocean Shipping hired Hyundai to build a massive oil tanker, the Atlantic Baron. They agreed on a price in U.S. dollars. But after the ink was dry, the value of the U.S. dollar unexpectedly cratered by 10%.

Worried about their bottom line, Hyundai demanded that North Ocean pay an extra $3 million to make up for the currency drop. They knew North Ocean had already lined up a lucrative charter for the tanker and couldn't afford any delays. To drive the point home, Hyundai threatened to stop construction entirely if the extra money wasn't paid.

This put North Ocean in an impossible bind:

- They had no reasonable alternative but to agree.

- Walking away meant breaching their own high-stakes charter contract.

- Finding another shipbuilder would take far too long and cost a fortune.

Backed into a corner, North Ocean caved. They agreed to the price hike "without prejudice" to their rights and paid the additional amount.

The Court's Decision and a Critical Lesson

When the case landed in court, the judge agreed that Hyundai’s threat to break the contract was a clear form of economic duress. The pressure was illegitimate, and it was the only reason North Ocean agreed to pay more. Hyundai had wrongfully exploited North Ocean's commercial vulnerability.

The core of economic duress is the absence of a realistic choice. When one party's illegitimate threat effectively removes the other party's free will, the resulting agreement cannot stand.

However, there was a twist. North Ocean waited eight months after the ship was delivered before they sued to get their money back. The court ruled that this delay amounted to an "affirmation" of the new contract terms. By waiting so long after the pressure was gone, they lost their right to void the contract.

This case offers two vital takeaways. First, threatening to breach a contract to extort more money is a textbook example of economic duress. Second, and just as important, victims of duress must act fast to challenge the contract once they're out from under the pressure. Delay can be fatal to a claim.

Physical Duress in Prenuptial Agreements

Compared to the nuances of economic pressure, physical duress is far more direct. A landmark example is Barton v Armstrong, a case that set a key precedent. Although it involved a business deal, the principles apply just as easily to personal contracts, like prenuptial agreements.

In this case, Armstrong threatened to murder Barton if he didn't sign a contract to buy out his shares in a company. Barton signed, but later claimed it was under duress. Armstrong fired back, arguing that Barton had good business reasons to sign the deal anyway and that the threat wasn't the only reason.

The court's ruling was crucial. It decided that for physical duress, the threat only needs to be one of the reasons for signing—not the sole or even primary reason. As long as the threat of violence contributed to the decision, the contract is voidable. This sets a much lower bar than economic duress, where the pressure often has to be the decisive factor.

Imagine this principle in the context of a prenup. If one partner is handed a prenuptial agreement days before the wedding and threatened with physical harm if they don't sign, that agreement is obviously tainted. Even if they might have considered signing a prenup under normal circumstances, the presence of a violent threat invalidates their consent entirely. These real-world examples show that whether the pressure is financial or physical, the law is designed to protect our fundamental right to enter a contract freely.

Drawing the Line Between Duress and Hard Bargaining

In the competitive world of business, negotiations get tough. They can be aggressive, uncomfortable, and downright stressful. But where does the law draw the line between a hard-nosed negotiation and illegal coercion?

Getting this right is crucial. It’s the difference between a binding (albeit tough) agreement and a contract that a court can tear up completely.

The distinction between legitimate hard bargaining and unlawful duress in contract law boils down to the kind of pressure being applied. Hard bargaining involves using lawful leverage to get the best deal you can. Duress, on the other hand, is about using an illegitimate threat that robs the other party of their free will.

Duress vs. Undue Influence: A Quick Analogy

To get a clearer picture, let's use a simple analogy. Think of duress as the classic "gun to the head" scenario. It’s a direct, obvious threat of harm—be it physical, economic, or otherwise—that forces someone into an agreement. The person’s will is totally overwhelmed by fear.

Undue influence is more like a manipulative "whisper in the ear." It happens when one party exploits a position of trust to improperly persuade the other. The pressure is subtle and psychological, slowly chipping away at the victim's judgment instead of delivering a single, jarring threat. This is common in relationships with a power imbalance, like a caregiver and an elderly patient.

While both can get a contract thrown out, they work differently. Duress breaks the will with force; undue influence bends it through manipulation.

What Is Legitimate Hard Bargaining?

Hard bargaining is the engine of commerce. It's the assertive—and sometimes aggressive—pursuit of a favorable deal. This isn't just legal; it's expected in most business settings.

Here are the hallmarks of legitimate hard bargaining:

- Leveraging a Strong Position: Using your market advantage, like being the only supplier in town, to negotiate higher prices is generally fair game.

- Driving a Hard Deal: Making a lowball offer or refusing to budge on your terms, even if it puts the other side in a tight spot, is part of the process.

- Threatening to Walk Away: Stating that you’ll end negotiations and take your business elsewhere is a perfectly acceptable tactic.

The key difference is that hard bargaining still leaves the other person with a choice, even if it’s a difficult one. They can accept the tough terms, walk away, or try to find another option. Duress strips away any reasonable choice. For example, clauses that limit liability can be negotiated aggressively; understanding what an exculpatory clause is helps you spot terms that are one-sided but likely still legal.

Hard bargaining pushes the boundaries of negotiation, but it respects the other party's ultimate freedom to consent. Duress shatters that freedom by introducing an illegitimate threat that makes refusal impossible.

Comparing the Concepts

To make the lines even clearer, here’s a simple table breaking down the key differences. This comparison shows how the type of pressure, the relationship between the parties, and the legal outcome vary in each situation.

| Feature | Duress | Undue Influence | Hard Bargaining |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Pressure | Illegitimate threats (e.g., harm, breach of contract) | Unfair persuasion and psychological manipulation | Lawful commercial pressure and leverage |

| Relationship | No special relationship required | A relationship of trust and confidence exists | Typically adversarial or arm's-length |

| Focus | Overcoming the victim's will through coercion | Abusing a position of trust to sway a decision | Achieving the best possible commercial terms |

| Legal Outcome | Contract is voidable by the victim | Contract is voidable by the victim | Contract is valid and enforceable |

Ultimately, the law gets that business can be a contact sport. But it draws a firm line when tactics cross from strategic pressure to wrongful coercion. Knowing exactly where that line is can protect you from making a fatal legal mistake—or becoming the victim of one.

Legal Remedies and Steps to Take

So, you've managed to prove you signed a contract under duress. What happens next? The contract doesn't just vanish into thin air. The law has a specific toolkit to fix the situation, and knowing your options is everything. The steps you take—and how fast you take them—will make or break your case. The goal here isn't to punish the other party, but to undo the damage from the coercion.

The main tool for this is called rescission. Think of it as a giant "undo" button for the contract. A court will effectively cancel the agreement, treating it as if it never existed in the first place.

This process is all about hitting rewind and putting everyone back where they started before the forced agreement was ever signed.

Wiping the Slate Clean

After a contract is rescinded, the court usually orders restitution. This is a straightforward but essential step: whatever was exchanged has to be returned. If you were forced to hand over money, you get it back. If you signed away a piece of property, the title is transferred back to you.

Restitution ensures no one gets to profit from a deal that was fundamentally broken from the start. It's the final step in turning back the clock.

The point of rescission and restitution isn’t to penalize the person who used duress. It’s to completely nullify the coerced transaction and restore both parties to their original, pre-contract positions as fairly as possible.

The Clock is Ticking—Act Fast

Here's the catch, and it's a big one: you have to move quickly. As soon as the duress is lifted—meaning the threat is gone and you’re no longer being coerced—a legal timer starts running. You have a very limited window to challenge the contract.

If you wait too long or act like the contract is still valid (say, by continuing to make payments or accepting benefits from it), a court can rule that you have affirmed or ratified the agreement. By not objecting right away, you’re basically sending a signal that you've accepted the deal, even if you were initially forced into it.

This is non-negotiable. As the North Ocean Shipping case showed, even a delay of a few months was enough for the court to rule that the victim had affirmed the contract. That hesitation cost them millions.

If you think you've signed something under duress, here’s what you need to do immediately:

- Gather Your Evidence: Collect every email, text message, or document that proves you were under illegitimate pressure.

- Talk to a Lawyer: Don't wait. An attorney can tell you if you have a strong claim and guide you through the right legal steps.

- Make it Official: Your lawyer will help you formally notify the other party, in writing, that you are voiding the contract because of duress.

Time is your enemy here. Any delay can turn a voidable contract into a legally binding one, slamming the door on your only escape route.

Frequently Asked Questions About Duress

When you're dealing with a contract that feels more like an ultimatum than an agreement, it's natural to have questions. Let's tackle some of the most common concerns that come up when legal duress is on the table.

Can a Threat to Sue Someone Be Considered Duress?

Usually, no. Threatening to file a legitimate lawsuit isn't considered duress. After all, the legal system exists to resolve disputes, and warning someone you intend to use it is a standard part of negotiations.

The line gets crossed when the threat is made in bad faith. For example, if someone threatens to sue you over a completely baseless claim just to pressure you into signing something, that could qualify. The key is that the pressure has to be improper to be considered duress.

How Long Do I Have to Cancel a Contract Signed Under Duress?

There's no single deadline, as it really depends on the jurisdiction. The most important thing is to act fast once the duress has ended.

If you wait too long or continue to act like the contract is valid after the threat is gone—say, by accepting payments or services—a court might rule that you’ve "affirmed" the deal.

By not moving to void the contract as soon as you're safely able to, you risk losing your right to cancel it. A delay can look like acceptance, which makes the contract legally binding.

Your best move is to get legal advice as quickly as possible to make sure you protect your rights.

What Is the Difference Between Duress and Fraud?

It all comes down to coercion versus deception.

Duress is about force. Someone uses threats or improper pressure to make you sign against your will. You know what the contract says, but you're being compelled to agree anyway.

Fraud is about trickery. Someone deceives you into signing by lying or hiding crucial information. You agree willingly, but your decision is based on a false understanding of the deal.

Think of it this way: duress hijacks your free will, while fraud corrupts your understanding of the facts.